Not too long ago, by beloved Blackberry went bust. I was a die-hard BB fanboy for years, but had been getting disillusioned; the OS always felt sluggish, the included browser was painfully slow, and the app store was vacant because developers preferred the much more lucrative Android and iPhone markets. So when my phone died, I didn’t go back–I joined the pack and got an iPhone.

Not too long ago, by beloved Blackberry went bust. I was a die-hard BB fanboy for years, but had been getting disillusioned; the OS always felt sluggish, the included browser was painfully slow, and the app store was vacant because developers preferred the much more lucrative Android and iPhone markets. So when my phone died, I didn’t go back–I joined the pack and got an iPhone.

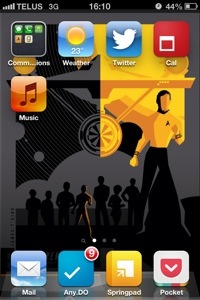

And I discovered something: I was using my Blackberry for very particular purposes, but I was missing out on a lot of innovative apps that would help my writing and my work. Now, I don’t intend to stay with the iPhone–I love my Android based Kobo Arc, so it makes sense to go with an Android phone–but these apps run on both systems. And I’ve found them indespensible:

Any.do

I’m a fan of checklists, and every time I upgrade a device, I search for a good list app. I’ve found the ultimate in Any.Do. It’s intuitive, robust, and it syncronises across my phone, Kobo and even an extension in my Chrome browser.

It couldn’t be simpler. When you launch the app you’ll see a list of your to-do items. You can add an item by pressing the + symbol, and the iPhone and Android devices accept voice input. You can then organise by due date (even pushing items to “someday”) or create folders. I have folders for Work, Personal and based on different projects with related tasks. When you complete a task, you can swipe to strike it off the list and–the fun part–shaking your phone will clear finished items.

Any.Do has also introduced a “Plan Your Day” feature, which will walk you through items that don’t have a due date so you can set priorities. Ask Any.Do to remind you in an hour, set it for tomorrow, or push it to next week. This is an excellent app, and I have it up on my work computer constantly through the day. If you want to keep track of progress and tend to forget the little details, get this now.

Any.Do has also built a Calendar app. I’m just getting used to it, but I like it a lot better than the native Iphone calendar. It’s clean, fresh, and simple–plus it lists your to-dos from Any.Do, and you can set it up to cycle through different images in the background. They’re also working on mail and notes apps, which I’m eager to try. Check them out!

Springpad

Which leads me to Springpad. A note taking app is essential for me, as I tend to have ideas in the most inconvenient places. If I don’t write it down right away, I’ll forget it–so having a note app on my phone is great. I don’t much like the native apps because they’re not that helpful, beyond writing stuff down. So I’m always on the look for a better one.

I settled on an app called Catch, which was simple to use, organised things into folders, and had a web plugin. Unfortunately, they’re gone now and no longer support the app.

Instead, I’m trying Springpad, and so far I really like it. You can organize notes into books as well, and it’s very easy to navigate between notebooks. The best part is the web plugin–set the shortcut on your toolbar and all of your notes are accessible from the browser. This is a godsend for writers; you get an idea on the bus, jot it down on your phone, and by the time you’re home you can launch Chrome and the notes are there, ready for you to put into your word processor.

Springpad also has a really nice interface. It’s not unlike Pinterest, and captures your notes in a series of tiles you can share. Springpad also has a Search feature, which lets you find other people’s notes, share ideas, and collaborate on projects. You could set up an account at work, and give each employee access–everyone adds their ideas and it’s all put down in one place. My wife and I use it for shopping: you can create a checklist, which we use for groceries, and both of us can access it at any time to add items we need.

This is note-taking meets social media, and it’s a really nice combo. After using it for only a couple weeks, I’m a convert.

I should also mention the note taking heavyweight, Evernote. Many people swear by it, and it’s got its good points. Personally though, I never liked it; I’ve found the interface dull and counterintuitive, and it just never seemed helpful to me. To each their own.

This is the one app I’m really excited about these days. I never really got into RSS readers, as they seemed to be pretty redundant; why download an article to read offline when the device you’re using is constantly online? The one application I can see is turing off your wifi or being in a location that doesn’t have access; not wanting to use your airtime is a good reason to use this app, but when wifi is so ubiquitous nowadays, it seems pointless. So I never bothered.

Until Pocket. I’ve been playing with this app for only a few days, but I’m hooked. I’m seeing the appeal of reading a headline or wanting to look something up, but not having the time to delve into it–Pocket lets you save that webpage or article and puts it in a queue for later reading. Again, simple as pie, but powerful if you use it right.

This app has solved a problem I didn’t realize I had. Although I don’t tweet much myself, I read twitter very often, and love getting interesting articles or hearing about releases from fellow Indies. When I come across a link I like, I tend to forward it to my email so I can check it out on a PC–many webpages just don’t display well on a phone browser.

Pocket allows me to get around that with no fuss. Just send it to the app, and it’s there when I’m ready. The best part is that Pocket has a web extension–I’m a fan of that integration, you can tell! If I come across a website I want to look at when I have more time, I can send that to pocket too. I’ve already got a nice list of things to catch up on.

Pocket also has some nice integration with other apps. I have yet to play with all the features, but you can send links to Pocket through Twitter, email, Digg, GReader, and more–over 300 apps and counting.

And here’s the really great news: Kobo recently announced that Pocket will be integrated in all its readers. You’ll be able to open your Reading Life to access all your Pocket pages. This brings e-reading to a new level; effectively it’s an electronic newspaper curates to your exact specifications. The feature is set to launch on September 13–I can’t wait to use it!

That’s it for today, but keep an eye on the blog for an upcoming interview with David A Hayden, and a review of Sarvet’s Wanderyar, by J. M. Ney Grimm!